Digital assets have been growing quickly, but in a volatile way, in recent years. From a market capitalization below $500 billion in 2019 to exceeding $3 trillion in 2021 and back down to $1 trillion in 2022, investor sentiment varies from a fear of missing out to extreme fear in a matter of weeks. It seems that institutions are allocating to digital assets more in venture capital and hedge funds than in owning the digital assets directly. By allocating in this way, investors leave the difficult issue of custody to the asset management firm.

For those interested in allocating to digital assets, most advisors suggest relatively small allocations. Bitwise models crypto at weights of 1%, 2.5% and 5% when added to a portfolio previously invested 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds.[1] In the five quarters ending March 2022,[2] venture capital firms allocated $44 billion to digital assets and the firms that program, custody, and trade them. Investments in digital asset hedge funds reached a peak of nearly $60 billion in the third quarter of 2021.[3] While institutional investment is growing in this area, investors are encouraged to use the same level of due diligence as they would for any other asset class. Just because returns were strong in 2020 and 2021 doesn’t mean that digital assets belong in your portfolio. It is always best to only invest in what you truly understand.

Whenever new technology comes along, there is a learning curve. The proponents of the new technology want to say it is revolutionary and that it is different this time. The digital asset and decentralized finance (DeFi) markets want to be transparent and unregulated, but there are perhaps reasons why this might not be the best way to build a market. Remember, the best way to build long-term wealth is to build a business that consumers value. While it may be tempting to get rich quick, it is often better to own a small part of a big business than to own a large part of a small business that never makes it to the long run.

What lessons can the digital asset and decentralized finance markets learn from the history of scandals in the centralized finance (CeFi) market?

- Asset-liability mismatches can ruin a firm when withdrawals are quicker than expected.

- It is always best to segregate client assets from firm assets.

- Leverage, illiquidity, and volatility do not mix well.

- Investment risk increases when you can print your own currency.

- Transparency of positions can and will be used against you by other market participants

What is the precedent for asset – liability mismatches? Let’s go back to the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s and early 1990s, where nearly one-third of US savings and loans failed. The S&Ls had the majority of their assets in longer term loans, such as mortgages, with fixed interest rates. As inflation rose and the Fed raised rates, the S&Ls had liabilities of deposit accounts with shorter duration and variable interest rates. When the income on assets is less than the interest rate on liabilities, investors post losses. The problem is that it is difficult to change the structure of the assets on the balance sheet, as homeowners are less likely to repay their mortgage during times of rising rates. If and when customers withdraw their deposits in search of higher rates elsewhere, the S&Ls experienced a bank run when deposits left much more quickly than the asset payments allowed. Digital assets have the same issue when they allow customer withdrawals on a same-day basis when the firm’s tokens are locked up. For example, in an attempt to earn a spread, a centralized digital asset exchange may pay their clients a 2% yield for depositing ether while the exchange stakes that ether in a long-term agreement to earn 4% or more. While the exchange is earning a substantial spread, there is a risk that the staked ether might not be available for withdrawal on a timely basis. When clients want their ether back today and it takes days or weeks to withdraw the ether from the staking program, this liquidity mismatch can destroy a firm. This sounds strangely like a fixed rate mortgage funded by variable rate debt, exactly the formula that led to the demise of the S&L industry thirty years ago. When depositors identify risk, either at an S&L or a centralized digital assets exchange, they withdraw quickly, leading to a bank run that ruins the firm.

It should be obvious by now that investors should perform both investment due diligence and operational due diligence before making an investment or engaging with a counterparty. A key part of operational due diligence is identifying and enforcing separation of duties and eliminating conflicts of interest. The 2008 bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers was a key factor driving the global financial crisis. The troubles at Lehman surrounded real estate and commercial mortgage-backed securities, funded at 30 times leverage. At larger levels of leverage, the margin of error for returns of the underlying assets declines. That is, at 30 times leverage, a decline of only 4% in the value of the firm’s assets more than wipes out the entire firm’s equity. While it may be prudent to sell assets and reduce leverage when losses begin, it is complicated to unwind large positions when market liquidity declines. The problem at Lehman Brothers that accelerated the contagion was that their hedge fund prime brokerage group rehypothecated $20 billion in assets. That is, Lehman used $20 billion in client assets to fund leveraged real estate positions where profits would accrue to Lehman. Investopedia defines rehypothecation as “when a lender uses an asset, supplied as collateral on a debt by a borrower, and applies its value to cover its own obligations.” Rehypothecation increases the amount of debt in the system, as the collateral is used not only to secure the loan to the hedge fund but an additional loan to the prime broker. When Lehman failed, their lenders sought to seize the collateral posted by the hedge funds even when the hedge funds were current on the terms of their loans. It took approximately five years for clients of Lehman’s prime brokerage to finally receive a return of their assets.[4]

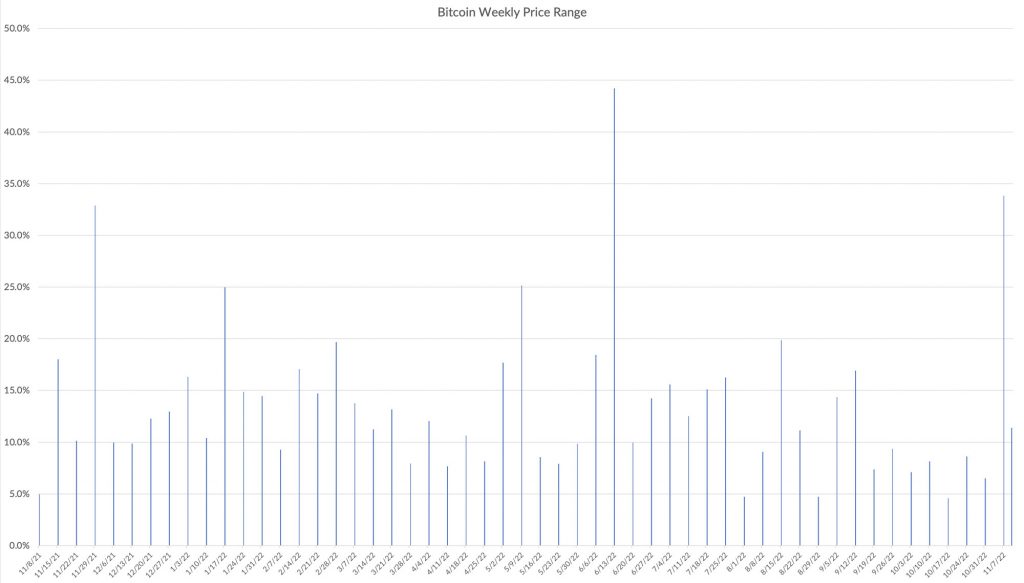

As the leveraged unwind of real estate during the GFC accelerated, global mortgage REITs experienced a 68% peak-to-trough drawdown.[5] Bitcoin and Ether recently experienced drawdowns of over 75% relative to their high prices exactly one year ago. These two blue-chip digital assets, which comprise nearly 60% of the value of the entire digital assets universe, have often posted annualized price volatility of 80% to over 100%. Much of the global digital assets business takes place outside of the US, in part due to market regulations. In the US stock market, reg T margin is limited to 2x, while regulated futures markets may offer as much as 5x leverage. Centralized digital asset exchanges prohibit US customers from trading at high levels of leverage. However, global digital asset market participants previously had access to 100x leverage, which recently has declined to 20x. Leverage and volatility don’t mix. Over the last twelve months, the median weekly range of bitcoin prices was 12%, ranging from a minimum of 4.6% to a maximum of over 33%. Traders using leverage of 21.5x would have either at least doubled their money or lost 100% of their equity in every single week of leveraged bitcoin trading over the last twelve months. If you do trade digital assets on a highly leveraged basis, it is risky to hold positions when you are away from the desk. That is, if you go to lunch or to sleep for the night, you will likely return to a highly profitable or a liquidated position. Beyond bitcoin and ether, many smaller capitalization digital assets experience even greater price volatility. The regular unwinding of highly leveraged trades is a key driver of the price volatility in the digital assets sector.

Source: Yahoo Finance, RIA Channel

Finally, as seen in both Terra USD/Luna and FTX, counterparties don’t view a self-minted currency as having substantial value. This observation is similar to the way the emerging markets debt (EMD) market separates hard currency from local currency bonds. When a sovereign borrower from an emerging country accesses the bond market, they have a choice of borrowing in hard currencies such as dollars or euros that they can’t print, or their home market currency, which they can print. There is clearly credit risk in hard currency debt, as the sovereign might not be able to access enough dollars or euros to service the debt. Sovereign borrowers with debt denominated in their home currency are unlikely to have credit risk, as they can simply print money to pay the principal and interest as scheduled. The key issue with local currency debt is the inflation rate, as the printing of the currency may debase the value of the bonds relative to dollars or euros. While you will receive the entire value of the bonds in local currency, the value of that currency may add up to much fewer dollars than anticipated. The same issue exists in the digital assets market, where loans collateralized by stablecoins, bitcoin, or ether may be seen as much higher quality backing than a token of the borrower’s own minting.

Finally, traditional hedge funds are typically wary of sharing the exact composition of their portfolios, especially when they are highly leveraged or concentrated in a small number of assets. Once other market participants know your specific holdings and the size of those holdings, it will be exceedingly difficult to exit those positions at a reasonable price, especially if you will be liquidating under duress. Because the digital assets universe is built largely on an ethos of transparency, exchanges and funds with transparent positions are encouraged to keep their positions diversified, liquid, and at lower levels of leverage.

While the digital asset market is exciting and innovative, participants need to remember the due diligence and risk management lessons that have been learned through a long history of market crises in the centralized finance market. It isn’t different this time. If digital assets are to transform the way global markets do business, the largest participants must build their businesses in a way that is sustainable in the long run. Digital assets won’t make it to the long run and reach mass adoption if the largest players don’t respect these risk management lessons, especially when the losers are the very customers they worked so hard to attract.

[1] https://bitwiseinvestments.com/crypto-market-insights/the-case-for-crypto-in-an-institutional-portfolio

[2] https://coingape.com/blockchain-industry-secures-12-billion-in-venture-capital/

[3] https://www.statista.com/statistics/1203383/cumulative-crypto-funds-aum-worldwide/

[4] https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2019/01/customer-and-employee-losses-in-lehmans-bankruptcy/

[5] https://realestate.wharton.upenn.edu/working-papers/the-global-financial-crisis-and-international-property-performance/