Let’s try and keep this simple; because the term hedging implies all sorts of sophisticated investing methods that the majority of advisor clients, including high net worth clients, are not going to understand. Non-deliverable forwards? Currency swaps? Who gets those things anyway? But let’s say you had a client who understands local currency bonds. It’s January. The Mexican peso is at its weakest level ever at 22. An investor buys the local government bonds, thinking the market is beating up way too much on Mexico. Just in case, he hedges his bet. Should the peso weaken further, he is protected. If it strengthens (which it did) he gets the currency gain. This is basically what a hedged ETF is doing. They are buying global securities and hedging the currency risks in one product.

In a recent webinar produced by the RIA Channel, Deutsche Asset Management and Accuvest Global Advisors explained when hedging works and when it’s not really needed. A replay of the webinar can be found here.

“When we speak to clients today one of the biggest questions we get is ‘what is next for the dollar?’ They want to know how to position tactically for it. Although the dollar has been pretty cyclical since it broke from gold in 1973, the last two years have been pretty tough for investors to figure out,” says Abby Woodham, ETF strategist for Deutsche Asset Management.

The dollar is not a problem for clients who are only investing in U.S. securities. But it absolutely is a problem for globally-minded investors who are holding foreign priced assets.

“Look for the dollar to remain strong over the next 12 months, so from a tactical perspective the dollar is still very attractive,” says Woodham, giving us a clue as to what Deutsche is thinking about the world’s most important currency. She is part of Deutsche’s in-house research team for their X-trackers funds, doing all the work on asset allocation and providing insights on global macro to fund managers.

When investors own international equities they are exposed to the underlying currency. Of course those currencies can have a surprising impact on a portfolio.

Here’s another example: Brexit. Anyone investing in the U.K. needed to be hedged against a pound sterling free fall or they took an even bigger hit to their portfolio.

“Immediately following the U.K. vote to leave the E.U., we saw a huge difference between the MSCI UK Hedged Return index and the MSCI U.K,” says Guillermo Cano, executive director at MSCI. A hedged strategy returned 19%. Unhedged? Zero percent.

Remember in 2009 when the dollar was dying and the euro was at 1.60. If you hedged against the euro getting stronger than that, you’ve made about 500 basis points annually on the exchange, notes David Garff, president of Accuvest Global Advisors.

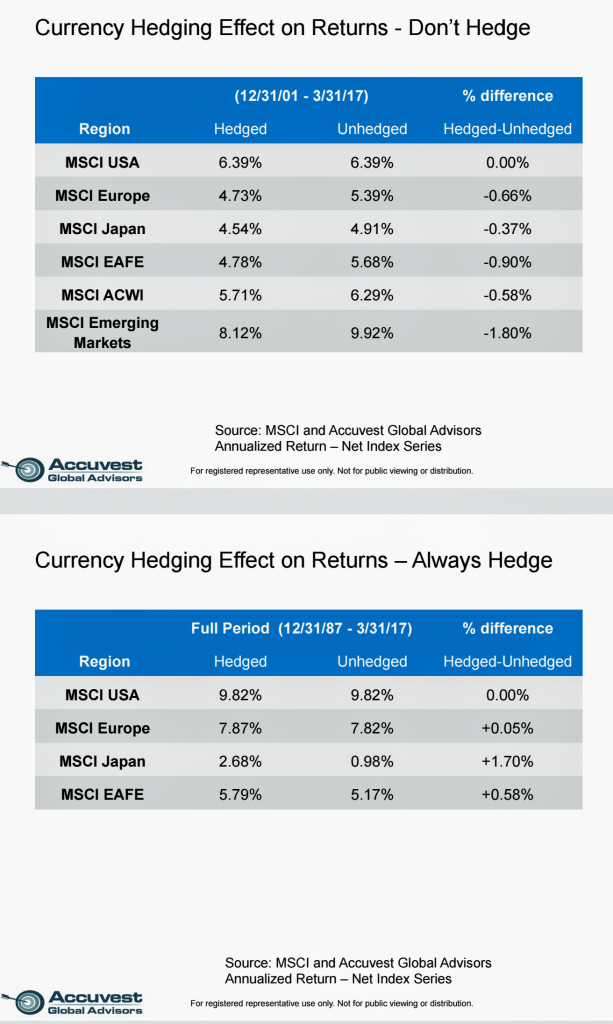

“This is where you return to the big picture question, which is to hedge or not to hedge your currency exposures,” Garff says. “We believe that the decision to hedge a currency depends on where you are in the cycle for risk. There are currency correlations which are relatively low in developed markets, and the emerging market currencies are more closely correlated with equities in their home markets. So if you’re in a scenario where you think emerging markets are going to run, you probably don’t need to be hedged. But if you’re uncertain then a hedged version might be ok.”

There are some misconceptions about currency returns in foreign ETFs and mutual funds. One is that currencies are a wash in the long run, so why bother hedging?

Over the long run, a reasonable expectation for the real return of most currencies is zero. Generally speaking, exchange rates should return to their equilibrium value over time. This implies that in the long run, the return of a hedged or unhedged investment in international equities should not be different. And in fact, over long periods of time, the return of currency hedged and unhedged developed market equity exposures tend to be very similar, according to Deutsche’s analysis.

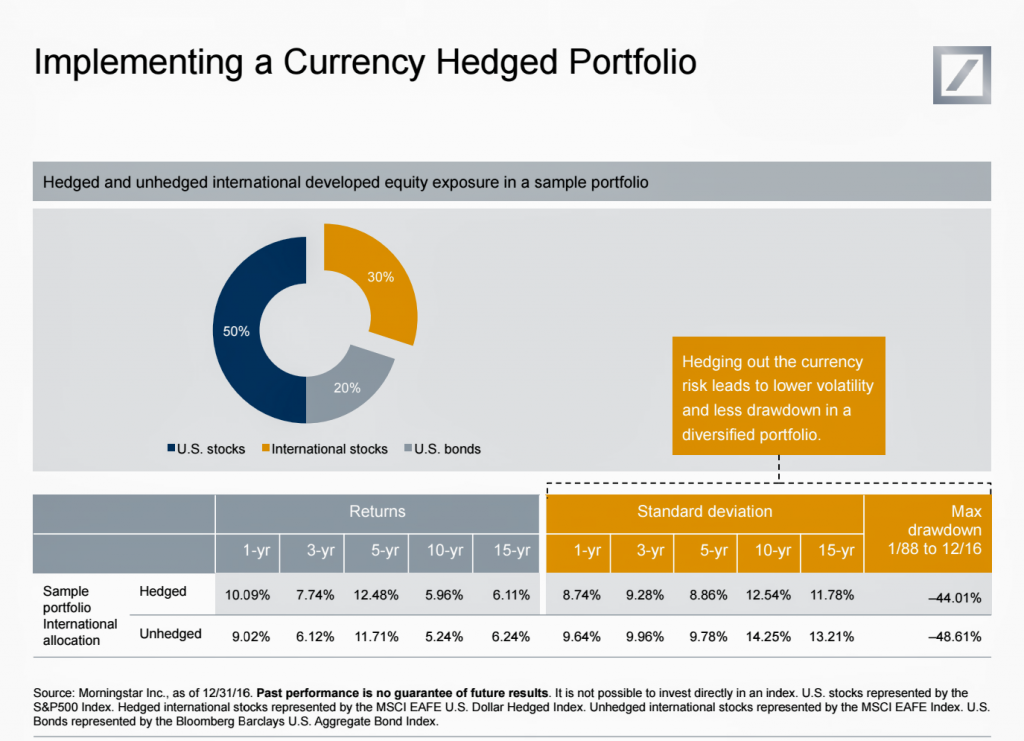

Another misconception is that currency exposure is a good portfolio diversifier.

According to modern portfolio theory, if assets are less-than-perfectly correlated with each other, combining them in a portfolio can result in lower overall volatility than the volatility of the assets on a standalone basis. Because currencies are not perfectly correlated with equity or bond returns, some investors view currencies as uncorrelated “noise” with the potential to reduce the overall volatility of an investment in global equities.

The diversification benefit of international equities is a function of the equities themselves, not their inherent currency risk.

Back to Mexico, the iShares MSCI Mexico (EWW 66,95 0,00 0,00%) ETF is up 9.7% year-to-date ending April 13 while the peso has helped by gaining 7.67%.

In markets that are going the other way, the currency of course has followed but not necessarily as an under-performer. For example, the VanEck Russia (Unfortunately, we could not get stock quote NYSEARCA: RSX this time.) ETF is down 5.5% this year, but the ruble has gained around 8% against the dollar.

It’s tricky business.

Deutsche has 25 hedged equity and four fixed income hedged ETFs. Hedging doesn’t always work. In terms of annualized returns, the Deutsche X-Trackers MSCI Emerging Markets Hedged (DBEM 24,93 -0,09 -0,34%) ETF underperforms the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets (EEM 40,84 +0,07 +0,17%) year-to-date, and over a one year and five year period.

On the other hand, their MSCI Japan Hedged (DBJP 74,27 -0,34 -0,46%) has performed better than the iShares MSCI Japan (EWJ 70,92 +0,27 +0,38%) over the last six months, 12 months and five year periods based on share price gains.

Woodham told webinar attendees that she expects three interest rate hikes by the Fed this year, with one out of the way already in March. She expects three more again next year. Higher rates means a stronger dollar versus emerging currencies in particular.

The European Central Bank is expected to start tapering next year as they start running out of bonds to buy in Germany, she says. They start raising rates in 2019, if her calculations are correct.

Within Europe, ECB tapering is what investors will start hearing about more. Those headlines will determine the euro’s direction. “Tapering is not necessarily a strengthening factor for the euro,” Woodham says. “The big driver is going to be two year Treasury-bund spreads. Given our expectations of higher rates in the U.S. and moderately higher rates in Europe, our forecast is parity by end of the year against the dollar but still stronger against the yen.”