“Changes in climate policies, new technologies, and growing physical risks will prompt reassessment of the value of virtually every financial asset” – Mark Carney (IMF Finance & Development, December 2019)[1]

Authors: Adam Bernstein & Jeff Gitterman

The climate is changing, and the effects of planetary warming and resulting climate change are manifold and growing. Climate change will increasingly influence the risk-reward profiles of all investments.

“For companies, this will mean taking climate considerations into account when looking at capital allocation, development of products or services, and supply-chain management, among other priorities.”[2] For investors, this will mean re-assessing business models for “resiliency rather than simply for efficiency.” It will also require re-visiting models and formulas used to quantify risks as well as their inputs, such as the cost of capital, and taking a closer look at investment vehicles for systemic climate risk. This includes pooled mortgages and municipal bonds in high risk areas vs. innovative structures like municipal bonds wrapped in catastrophe bonds, allowing investors to hold municipal debt without worrying about the hard to assess local climate risks on tax revenues.[3]

Advisors need to understand how climate change may affect the investments they offer to their clients, as well as how climate change may impact other aspects of a client’s overall net worth. This paper aims to provide support to help an advisor proactively engage with their providers and other experts to better protect client capital.

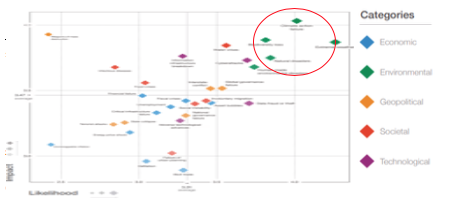

World Economic Forum – Global Risk Landscape 2020 –[4]

The risks with the highest impact and likelihood are all climate and weather related.

Source: Global Risk Report 2020. World Economic Forum – 15th edition

Climate related risk is at the top of the World Economic Forum’s global risk survey for 2020, followed by cyber-attacks, interstate conflict, and asset bubbles. Yet, it is still not widely considered to be a major imminent threat to portfolio success. This is partly because disclosure of climate-related impacts at the corporate level is still insufficient. “Risks that are priced are generally well disclosed and are better understood by investors. Risks that are unpriced are generally undisclosed or poorly disclosed.”[5] Prices drive human behavior, and therefore the information gap is preventing an adequate response from investors, consumers, and other stakeholders. [6]

Climate risk is particularly challenging because it is relevant to many sectors and industries, although its impacts on these stakeholders will differ. An informed conversation on climate and how it might affect investments, or a specific business must involve a diverse array of stakeholders and industry experts. These types of cross-industry collaborations are not currently the industry standard, but will be vital to assess interdisciplinary risks. This paper has been written by collecting data from a variety of sources and industries in order to help illustrate the importance of a cross-disciplinary approach.

Climate Change Risks and Impacts

On an interconnected planet, where the ramifications of climate change are multi-faceted with no opportunity for complete evasion, it is clear that people, municipalities, companies and investments will all be affected. The degree of impact is imbued with uncertainty depending on sectors and geographies.

Current decision maker experiences are based on relative climate stability, with a variable climate being outside of most planning processes. A changing climate will require decision-makers to understand and embrace the probabilistic nature of climate risk and address possible biases and outdated mental models.[7]

Within the overall concept of climate risk, there are two primary underlying risk classifications:

1.) Transition Risks

Over time, the world economy will decarbonize as renewables become more cost effective than hydrocarbons. Through the transitional period, companies will experience effects from changes in policy, shifts in regulation, and potential increases in litigation. In addition, costs associated with deriving energy from alternative sources and changes in consumer demand for certain products and services will impact business models. [8]

Regulatory bodies are increasingly integrating climate change into polices and legislation. In fact, “more than 580 legislative and 840 executive acts have occurred globally as of 2018, a 26% compounded annual growth rate since 1999.”[9] Concurrently, large rating agencies and data firms such as S&P,[10] Moody’s,[11] MSCI,[12] and Bloomberg,[13] among others, have been purchasing climate data firms and implementing climate risk into their standard ratings and research. For example, MSCI acquired Carbon Delta in 2019, and subsequently announced the launch of their new climate value-at-risk tool. Climate VAR is designed to provide a forward-looking and return-based valuation assessment to measure climate related risks and opportunities in an investment portfolio. Tools like these are for investors who don’t have the means to cultivate their own climate-centric research partnerships or hire climate scientists.[14]

It is important to remember that climate risk is not cyclical, meaning it will reflect “higher long-lasting structural risks in particular geographies or sectors,”[15] eventually causing repricing of debt instruments and a permanent destruction of capital. Therefore, companies already strategically exploring these topics and likely scenarios, and disclosing their risks and opportunities, will likely fare better than those avoiding grappling with the challenges.

2.) Physical Risks

Physical climate risks represent the tangible manifestations of a changing climate and the associated costs, which all organizations and populations will likely experience in some form or another. “Physical risks include both chronic changes, or long-term shifts in climate patterns, as well as acute events, which may increase in severity or frequency.”[16] Chronic risks can be felt in increasing heat, drought, and loss of water access, whereas acute risks will be experienced as wildfires, hurricanes, and flooding.

By way of example, a recent McKinsey report noted that by 2030, heatwave temperatures in certain areas will exceed the survivability threshold, for the first time in human history, for a healthy human being resting in the shade (a standard measure of livability excluding the effects of air conditioners). This is a new phase of human history and can affect 160-200 million people by 2030.[17]

A broader impact will come from non-lethal heat that reduces human ability to work outside. The same McKinsey report stated that 700 million to 1.2 Billion people could be impacted by 2050, such that the average annual outdoor working hours lost would increase from 10% today to 20% in certain areas. For context, in India as of 2017, “heat-exposed” work drove around 50% of GDP, employing around 75% of the labor force. [18]

The effects of acute events may lead to immediate, but likely short-term price changes. However, chronic impacts can devalue an asset over the longer-term as well as affecting potential future value creation.[19] Around the world, physical assets like buildings could be damaged or destroyed by extreme weather or devalued over time by chronic impacts. For the first time we are hearing asset management firms discuss abandonment strategies for certain geographically located and carbon intensive assets. At the moment, 200 billion dollars of residential real estate in Florida is located less than 1.8 meters above hightide.[20] Florida’s economy relies on real estate, which accounts for 22% of GDP and 30% of local tax revenue. In the U.S. overall, primary residences represent 42% of median homeowner wealth. Residences located in higher risk areas may face re-pricing and difficulties with securing mortgages.[21]

DEFINING CLIMATE RISK FOR THE INVESTMENT WORLD

The Current State of ESG and Climate Reporting

The importance of non-financial information in making financial decisions, often referred to as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, is now broadly recognized across the investment world. A growing body of applied and academic research underpins how ESG data helps investors better understand the risk and opportunity drivers of a company or financial investment.

From a risk perspective, ESG information is now indispensable. In fact, Bank of America found that 24 ESG controversies had “resulted in peak to trough market value losses of $534bn as the share prices of the companies involved sank relative to the S&P 500 over the following 12 months.”[22] Some of these controversies are arguably ephemeral, whereas, as previously stated, risks to certain sectors and companies from climate change effects may be more fundamental and enduring.

Today, the climate risks we have discussed in this paper are mostly not captured by current ESG data, strategies, or traditional data sources such as Bloomberg, FactSet, Morningstar etc., although change is coming with the ongoing acquisitions of specialized data firms and consolidation within the financial data industry. When assessing climate risk, the asset management industry primarily views transition risks through the lens of metrics such as carbon foot printing, GHG scope emissions, and carbon intensity. Such data has become more readily available, largely owing to improved corporate disclosures, data collection, and modeling from ESG data providers. Yet, while useful in certain contexts, this information does not incorporate the full financial implications of climate change for a given organization, limiting its decision-usefulness to an investor.[23] Physical risks are even less well disclosed than transition risks, resulting in a gap in many corporate risk models, and subsequently in investment portfolio decision-making.

The establishment of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) is one initiative aiming to close the gap between existing reporting and the needs of the financial markets. Subsequent to the release of TCFD’s recommendations, “the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) collaborated intensively to assess alignment on the TCFD’s principles, recommended disclosures, and illustrative example metrics.”[24] It is hoped that this will provide greater clarity for companies in disclosing climate-related information, thereby improving the overall quality of information available to the market, which should translate into greater risk awareness, capacity to price risks and, subsequently, enhanced investment strategies.

Climate-Aware Funds and Strategies

As awareness and data availability increases, asset managers are increasingly adopting a climate lens in their research, security selection, and portfolio construction processes. This is critical because assets with greater embedded climate risk are likely to face greater long-term drawdown risk.

Traditional investments and benchmarks are riddled with climate risks. For example, a coal-fired power plant might look like a good investment because it currently generates strong cash flows and had historically offered strong returns. Factor in the political, economic, and regulatory trends that are phasing out the use of coal as a staple power source, and the power plant looks like a much riskier investment. [25]

Selecting climate-aware strategies for a portfolio comes with complications, including getting to grips with the terminology. When trying to analyze the mutual fund, ETF, and SMA universe it is easy to get confused by the profusion of climate-related monikers; green funds, low emission, low carbon, fossil fuel free, fossil fuel reserve free, clean energy, and renewable energy, to name a few.

To simplify, we categorize all climate strategies into either “climate adaptation” or “climate mitigation.”

- Climate mitigation: As the term suggests, such a strategy is focused on attempts to mitigate the effects of climate change, for example by managing portfolio emissions through excluding or reducing investment in companies with high emissions. This is a best-in-class approach that generally invests in the same companies and sectors as its traditional benchmark, but at different weights. The MSCI ACWI low Carbon ETF (CRBN) is an example of this type of climate strategy.

- Climate Adaptation: These strategies look to avoid physical climate risks and invest in companies creating solutions to climate issues and/or those likely to be a net beneficiary from a changing climate. This category will not invest in every asset class, geography, or sector, and may use negative and positive screens to focus on companies with resilient business models and supply chains. Climate adaptation strategies will likely look very different to traditional benchmarks. Funds that fall under this strategy type include fossil-fuel-free, clean energy, and renewable energy funds. The Hartford Environmental Opportunities fund (HEOIX) is an example of this type of strategy.

As an Investor trying to select managers or create a climate aware investment offering, understanding the differences in climate fund strategies will help identify those that best align with your client needs. How a firm chooses to use such strategies will depend on its perception of our proximity to major climate events and the extent to which it believes these events will affect asset prices. Timing and magnitude can be estimated and iterated, but it is up to investors, and by extension, advisors, to assign an appropriate weight to these risks. Clarifying a climate change stance is a critical precursor to effectively performing manager due diligence and creating or selecting portfolios that address climate change.

Presently, few mutual funds and strategies explicitly make climate change a core mandate in their official documentation. However, as explained above, it is possible to identify all manner of products that broadly incorporate these risks, albeit at varying degrees. The next generation of asset managers and products will be climate-centric, and there are already examples of leading firms acquiring or organically developing climate research and products.

- Allianz Global Investors and PIMCO are both owned by Allianz SE the large multinational insurance company and asset management company. Allianz SE is known for its climate risk modeling capabilities. This core competency is shared with the asset management arms to bolster existing funds and to help create new innovative ones. PIMCO has recently launched its climate bond fund that invests in strategic fixed income securities that will benefit from the long-term dynamics of climate change. The strategy can invest in Green labeled and unlabeled bonds, renewable energy projects, municipality owned water systems, green real estate, and low-carbon transportation projects. [26]

- Wellington Management recently entered into a formal research partnership with one of the leading climate change think tanks in the world, the Woods Hole Research Center, to develop proprietary tools and research. Subsequently, they have launched climate adaptation SMA strategy. The strategy invests thematically in companies that will help society adapt to the physical effects of climate change with a focus on six key climate variables to the capital markets: heat, drought, wildfire, hurricanes, flooding and water access. [27]

- Neuberger Berman announced a firm-wide climate corporate strategy with its major hire of a climate scientist group that reviewed the imbedded climate risk to the companies 304bn portfolio in 2019. The group assessed what the financial implications might be to the firm’s investments in a 2-degree warming scenario and built out internal climate risk tools to be used by the risk and investment teams. [28]

Asset Class Case Studies

Despite all this activity, climate change is still viewed by many as a future issue and not something happening right now. The remainder of this paper covers several asset class case studies that illustrate current impacts of climate change to provide advisors actionable examples that can be shared with clients.

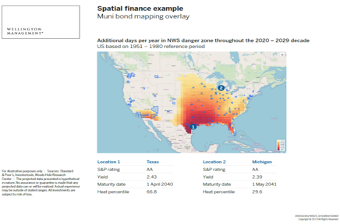

The Immovability of Municipal Bonds

The graph below was created by Wellington Management and the Woods Hole Research Center. It depicts two municipal bonds with similar ratings, maturities, and yields, with location being the only differentiator. One bond is from a municipality in Michigan, and the other is from a municipality in Texas. Overlaid on the map is the heat index, representing U.S. projected temperatures for 2020-2029 based on a 1951-1980 reference period. The area in red represents extreme danger of heat stroke. As an example, if the air temperature is 96°F and the relative humidity is 65%, the heat index would show red indicating extreme danger.[29] All things being equal, which bond looks more attractive and more likely to realize the cash flow of normal operations?

Source: Wellington Management – Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Capital Markets

Real Estate and Commercial Mortgages

While any business reliant on a physical building is exposed to climate risk, overall disruption in the real estate market is most pressing, as buildings are the business. Real assets may be exposed to rising sea levels, flooding, heatwaves, water shortages and storms, as well as indirect effects. [30]

When risk avoidance is impossible, mitigation and adaption become imperative. Effective mitigation requires an accurate assessment of risks and potential damages to expedite returning a building to normal operations in the aftermath of an acute event. [31]

The climate data company Four Twenty Seven recently applied its scoring model of asset-level climate risk to GeoPhy’s database of listed real estate investment trusts’ (REITs) holdings to create the first global, scientific assessment of REITs’ exposure to climate risk. The dataset includes detailed, projections of climate impacts from floods, extreme precipitation, sea level rise, and exposure to hurricane-force winds. The database also includes water stress and heat stress for over 73,500 properties owned by 321 listed REITs.[32] Checking whether REITs are screened for physical risks is now table stakes for real estate due diligence.

Source: Four Twenty Seven; Climate risk, Real Estate, and Bottom Line Press Release.

Going forward, homeowners may need to adjust assumptions about taking on long-term mortgages in certain geographies. “In Florida, the average annual losses for residential real estate due to storm surge from hurricanes amounts to $2 billion today. This is projected to increase to about $3 billion to $4.5 billion by 2050.”[33] Rough estimates suggest that the price effects discussed above could impact property tax revenue in some of the most affected counties by about 15% to 30%.[34] “Unfortunately, homeowners cannot protect against the risk of devaluation with insurance. While mortgages can have 30-year terms, insurance is repriced annually or every two years. This duration mismatch means current risk signals from insurance premiums might not build in accurate risk over an asset’s lifetime, which may lead to poor investment decisions.”[35]

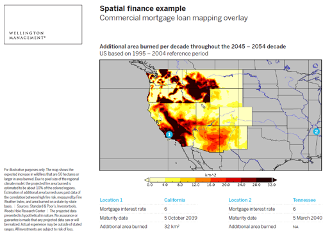

In another example from Wellington Management and the Woods Hole Research Center, the below graph demonstrates the climate risk of two commercial mortgages with similar interest rates and maturities, where, again, the difference is the locations of the properties. One mortgage represents a building in California and the other a building in Tennessee. Overlaid on the map is the expected increase in wildfires that are 50 hectares or larger in area burned based on wildfire data from 1995-2004, and projecting out to 2045-2054. The area in red represents a high likelihood of large fires. You can see from the graphic that the mortgage bond located in California is embedded with substantially more fire risk than the mortgage bond in Tennessee. [36] Geospatial analysis is an essential part of assigning physical climate risks to investments, because these risks are global, but they manifest locally.

Source: Source: Wellington Management – Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Capital Markets

Public Equities

Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), is a publicly listed utility that plays a large role in facilitating California’s transition to a low-carbon economy. California’s Renewable Portfolio Standard Law requires utilities to generate 60% of their supplied power from renewable sources by 2030. PG&E has vast regional coverage, serving roughly six million Northern California residents, and it is one of the country’s most renewable utilities based on total dollars invested. [37]

PG&E is a perfect example of a company that at face value had all the marks of being a great sustainable and climate aware investment. Many climate mitigation strategies held PG&E for is large role in de-carbonizing California. An analysis from Morningstar Direct showed that 3.7% of ESG funds held PG&E at the start of 2019, but climate adaptation strategies that specifically look at physical risks did not invest in this company. In this situation, fire risk was well documented in the annual reports and touted extensively by management.[38] Nevertheless, many investors ignored this risk, and PG&E lost about $1.4 Billion dollars in four trading days in the wake of the blaze in Sonoma county California, and filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy shortly thereafter.

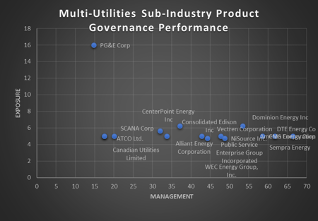

Below is a graph created using Sustainalytics data, demonstrating the high-risk exposure and poor risk management of PG&E ahead of its bankruptcy. Out of its entire universe of 2,952 companies, it scored dead last in product governance, a Sustainalytics category that encompasses quality and safety events such as fire risk.

Source: Sustainalytics

Taking Action

We see a connection between the risks investors are facing due to climate change and the factors that led to the subprime mortgage crisis: an under-informed public, agency risk, inadequate regulation and oversight, and more opportunities to go long than go short, among other factors.[39]

The current political rhetoric can be distracting, especially in the U.S. However, the evidence is mounting, and advisors and individual investors should make every effort to understand the risks in their portfolios over the short and long term – and adapt their allocations accordingly.

Portfolio risk assessments must go beyond traditional portfolio risk metrics, ESG integration, and screening processes to incorporate scenario analyses that understand the probabilistic nature of climate risk and be mindful of possible biases and outdated mental models. These sophisticated procedures must be incorporated into upfront manager due diligence, asset allocation, as well as ongoing portfolio monitoring.

While this paper has focused mostly on risk, it is critical to note that change also presents opportunities for companies that orient their business models, products and services toward the needs of a low-carbon economy. Better informed investors will help to encourage all countries, regions, companies, and municipalities to utilize climate science to better prepare for the risks and opportunities presented by climate change.

Disclosure:

The information contained herein should not be construed as personalized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that the views and opinions expressed in this article will come to pass. Investing in the stock market involves gains and losses and may not be suitable for all investors. Information presented herein is subject to change without notice and should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security.

Investment advisory services are offered through Gitterman Wealth Management, LLC an independent investment advisory firm registered with the SEC (CRD 153062). Associated persons of Gitterman Wealth Management, LLC are licensed with and offer securities through Vanderbilt Securities, LLC, member FINRA/SIPC, registered with MSRB (CRD 5953). Gitterman Wealth Management, LLC and Vanderbilt Securities, LLC are separate and distinct federally regulated entities. For more information see www.adviserinfo.sec.gov.

[1] IMF Finance & Development – Mark Carney, December 2019

[2] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 31.

[3] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 31.

[4] Global Risk Report 2020. World Economic Forum – 15th edition

[5] SASB Conceptual Framework – Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) – 2017

*Representative Concentration Pathways: Climate impact research makes extensive use of scenarios. Four “Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) act as standardized inputs to climate models. RCP 8.5 predicts global average warming of 2.3 degrees Celsius by 2050.

[6] Global Risk Report 2020. World Economic Forum – 15th edition

[7] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 114.

[8] Physical Risks of Climate Change (P-ROCC), September 2019 report. A Wellington and CalPERS collaboration. Pg. 1-2

[9]Climate Change Laws of the World database, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. As of 31 December 2018.

[10]https://www.robecosam.com/en/media/press-releases/2020/sp-global-finalizes-acquisition-of-the-sam-esg-ratings-and-esg-benchmarking-business-from-robecosam.html

[11]https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/24/climate/moodys-ratings-climate-change-data.html

[12]https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/trending/akwmzn8v879owls3pjvrda2

[13]https://www.bloomberg.com/impact/approach/thought-leadership/

[14]https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200205005197/en/MSCI-Launches-Solution-Enabling-Investors-Assess-Exposure

[15]Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 47.

[16] Physical Risks of Climate Change (P-ROCC), September 2019 report. A Wellington and CalPERS collaboration. Pg. 1

[17] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 23.

[18] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 23.

[19] Physical Risks of Climate Change (P-ROCC), September 2019 report. A Wellington and CalPERS collaboration. Pg. 1-2

[20] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. IX

[21] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. IX.

[22] https://www.ft.com/content/3f1d44d9-094f-4700-989f-616e27c89599

[23] Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures – Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure, June 2017 p1

[24] https://corporatereportingdialogue.com/publication/driving-alignment-in-climate-related-reporting/

[25] https://www.ft.com/content/820e079a-4439-11ea-9a2a-98980971c1ff

[26] PIMCO Climate bond fund Q1 2020 deck

[27] Wellington Management Climate Adaptation SMA due diligence

[28] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-18/neuberger-berman-climate-review-finds-big-holes-in-readiness

[29] https://www.weather.gov/safety/heat-index

[30] Vert Asset Management – Sam Adam 2020

[31] Climate Risk, Real Estate, and the Bottom Line’, Geophy & 427 2018 Report.American Homes 4 Rent. American Homes 4 Rent Reports Third Quarter 2017 Financial and Operating Results. 7 November 2017. Press Release

[32] http://427mt.com/2018/10/11/climate-risk-real-estate-investment-trusts/

[33] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 19.

[34] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 19.

[35] Climate risk and response: Physical hazards and socioeconomic impacts; By Jonathan Woetzel, Dickon Pinner, Hamid Samandari, Hauke Engel, Mekala Krishnan, Brodie Boland, and Carter Powis – January 2020 report. Pg. 78.

[36] Source: Wellington Management – Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Capital Markets

[37] https://investor.gittermanwealth.com/pge-a-case-for-active-vs-passive-esg-investing/

[38] https://www.wsj.com/articles/pg-e-knew-for-years-its-lines-could-spark-wildfires-and-didnt-fix-them-11562768885

[39] Wellington Management – Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Capital Markets